Doug Caplan, born in Montreal in 1965, has dedicated much of his life to navigating the worlds of analog and digital photography. He got his first camera as a teenager—a Polaroid instant, complete with the scent of film chemicals and the thrill of waiting for an image to appear. But like many early hobbies, it faded. Life moved on. He didn’t return to photography until the 1990s, after marriage, when something quiet but persistent called him back.

He started with a Nikon, but it didn’t sit right. Too polished. Too modern. Caplan wanted something that gave him more control and less interference. He turned to a Mamiya M645, a medium format camera from the 1970s, with a stripped-down design that forced focus—literally and creatively. That camera changed things. It slowed him down, made him think, made him notice. From there, Caplan took classes at Ampro Photo Workshops in Vancouver. Darkroom work. Medium format skills. Real hands-on learning. That’s when photography stopped being a passing interest and became something deeper.

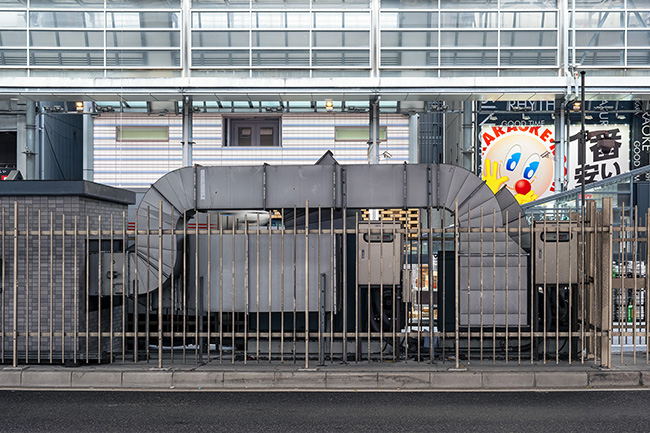

Caplan’s work today moves between analog and digital, but his sensibility stays rooted in the slow, deliberate approach of medium format film. He doesn’t chase perfection. He chases tension—the places where form breaks down, where something strange sneaks into the ordinary. His photograph The Absurdity of Existence is a good example of this.

Shot in Osaka, the image is full of clean lines and hard edges. Architecture with rules. Surfaces that don’t surprise. It’s a city that seems locked in logic. But Caplan finds something else. Right in the center of that neat geometry is a face—big, colorful, grinning. You don’t know why it’s there, or what it means. It doesn’t belong. But the more you look, the more it does.

There’s humor in that photo, but not the kind that’s trying to be funny. It’s the humor of absurdity. A reminder that no matter how precise we make our environments, life has a way of poking through. Caplan doesn’t frame absurdity as a disruption; he presents it as part of the system. That grinning face doesn’t ruin the composition—it finishes it.

This approach runs through much of his work. Caplan is drawn to contradiction, to moments where the built environment gets weird, or too human, or unexpectedly poetic. His camera isn’t searching for beauty in the traditional sense. It’s looking for something slightly off. A misfit detail. A structure that hints at something else. A sign that maybe the world isn’t as tightly arranged as it pretends to be.

He often shoots in urban settings—Japan, Canada, parts of the U.S.—where visual patterns dominate. Grids. Roads. Signage. But in those places, Caplan seems to find softness, humor, sometimes even melancholy. His photographs suggest that even the most controlled spaces are not immune to surprise.

Caplan’s style is stripped-down, like the camera he first returned to. He doesn’t over-edit. He avoids heavy digital manipulation. His colors are deliberate, but not over-saturated. His compositions are precise, but not rigid. There’s room in the frame for things to feel strange.

One of the quieter strengths of his work is how it resists easy interpretation. You can look at The Absurdity of Existence and smile, but also feel unsettled. Is the face mocking the city? Is it part of some forgotten ad campaign? Is it just a fluke? Caplan leaves it open, and that openness is what stays with you.

Doug Caplan isn’t trying to make bold statements or push trends. He’s looking at the world carefully and showing you what you might have missed. A crack in the grid. A burst of color where none should be. A joke hiding in the design.

He’s not in a rush. He doesn’t shoot for volume. He doesn’t flood feeds with images. Caplan’s pace matches his process—deliberate, thoughtful, and often surprisingly funny. His work reminds us that photography isn’t just about capturing what’s there. It’s about paying attention to what shouldn’t be, but is.

And in that, maybe, lies the absurd beauty of the whole thing.