Mojgan McClusky didn’t come to art through the classroom. She came to it through need. Born in Iran and arriving in the United States as a teenager, she landed in a country where she didn’t speak the language and didn’t know the rules. What she did have was a drive to create—something that had carried her through a childhood where self-expression had been scarce and confidence even scarcer. Art gave her a space to process what couldn’t be spoken. It gave her a voice before she had words.

Over time, that voice grew more sure of itself. But McClusky never abandoned the idea that real art happens in the spaces between language and logic. Her work isn’t bound by the neat categories of genre or style. It’s loose, emotional, and intuitive. Her paintings are explorations of memory, subconscious feeling, and the universal tug of time. Each one invites a quiet confrontation—with self, with story, with the rawness that hides just below the surface of daily life.

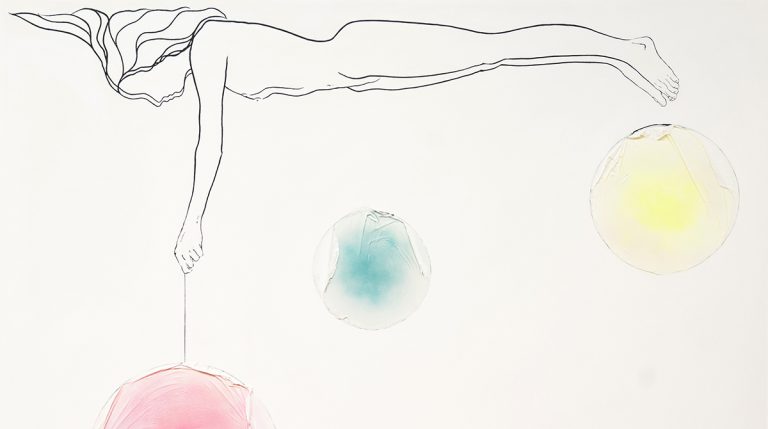

“Ascension” is a large work—72 by 96 inches. It’s the kind of painting that pulls you in before your brain catches up. At first glance, it’s dreamlike, almost weightless. But spend a little more time, and the tension underneath becomes harder to ignore.

The central image is a suspended figure reaching upward, almost floating, as if caught in the pause between falling and flying. Above the figure are three pale spheres—soft, almost ghostly shapes that seem just out of reach. These orbs represent past, present, and future. They’re not clearly labeled, but they don’t need to be. The viewer feels their meaning in the way the figure stretches, as if trying to reclaim something lost or grasp what’s just ahead.

That act of reaching is what holds the whole painting together. It’s delicate, but it’s not passive. There’s effort in the gesture. Struggle, even. And when you know McClusky’s story—when you understand that this image was inspired by a childhood memory of chasing a balloon into a dangerous place—the scene takes on another layer of depth. It becomes a metaphor not just for time, but for risk, for longing, for the fragile boundary between safety and possibility.

The number three has a special weight in this piece. For McClusky, it’s a personal and spiritual symbol. Here, it anchors the painting—not just visually, but emotionally. The three spheres aren’t evenly spaced or brightly colored. They’re subtle, part of the atmosphere more than they are solid objects. But they structure the composition like a kind of silent rhythm. You don’t notice them at first, but once you do, they’re hard to forget.

What’s also striking is the use of mixed media. McClusky doesn’t limit herself to paint. The texture of the canvas changes across the surface. Some areas are built up and almost sculptural, while others are sheer and transparent. It’s a mix that mirrors memory itself—some parts vivid, some fading, some confused. And because of that, “Ascension” feels lived in. Not illustrated. Not designed. Felt.

There’s no literal storytelling here. No clean narrative. But there’s a sense of emotional movement, from the base of the canvas—darker, heavier—to the top, which opens up into light. That vertical movement creates the sense of rising, but it’s not heroic. It’s hesitant, searching. Like climbing out of a place you’ve been for too long, unsure of what’s at the top.

In many ways, “Ascension” encapsulates McClusky’s approach to painting. It’s not about showing something. It’s about sharing something—an inner moment, a sensation, a memory that can’t quite be pinned down but still demands recognition. For her, painting is a kind of silent dialogue with the viewer. It bypasses the rational brain and aims straight for that part of us that remembers dreams or feels grief before we understand its cause.

This isn’t easy art. But it’s deeply human. It’s the kind of work that stays with you—not because of what it says, but because of what it lets you feel. And in McClusky’s world, that’s the point. When words fall short, image takes over. When the past threatens to blur, art becomes a way to hold on. “Ascension” doesn’t offer clear answers. But it asks honest questions. And sometimes, that’s all we need.