[ad_1]

When New York art dealer Marianne Boesky makes her debut at the TEFAF Maastricht fair in the Netherlands next week, she will present an intriguing pairing of two artists born a century apart.

One is Danielle Mckinney, an emerging artist whom Boesky represents and whose prices are rising rapidly. (A 2021 canvas fetched about $340,000 at Christie’s in London this week.) The other is the great American realist Edward Hopper (1882-1967), whose painting Chop Suey (1929) sold for $91.9 million at Christie’s in 2018, a record for a historical American painting.

Hopper is a logical choice for a fair that focuses on centuries-old treasures. Mckinney, a 43-year-old rising star, is a bit more surprising. But TEFAF, which is often termed the “grande dame of art fairs,” leaned into contemporary art in recent years, as wet paint became all the rage for the rich.

Edward Hopper, Gloucester Houses (Houses on a Hill), 1926 or 1928. @Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen

How did the pairing come about? Boesky and Mckinney visited the Whitney Museum’s 2022 Hopper retrospective, a gallery spokesperson said, and the two artists’ focus on cinematic light and solitude became apparent.

Being shown in the context of Hopper’s historic work could elevate Mckinney, who started painting just five years ago. But Hopper may also benefit by being seen in the context of a hot ultra-contemporary artist. It’s win-win. It’s also something we may see more of in coming years. Allow me to explain.

All through my art journalism career, I’ve heard stories about a great shift in the market for traditional American art and decorative objects. Once a key collecting category, with robust auction departments, hungry collectors, and record sales, historical American art was hit hard by the 2008 financial crisis. I’ve long wondered if the field will ever recover.

Danielle Mckinney, Lumen (2025) @Danielle Mckinney. Courtesy: Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen

Boesky’s Hopper-Mckinney duet is one of a number of signs that may be happening. The Wolf Family Collection, a massive trove of American art and decorative objects assembled over generations, sold for $68 million at Sotheby’s last April, surpassing its high estimate by 140 percent. The haul at Christie’s annual sales of 19th-century American art almost quadrupled, from 2022, when they earned $4.96 million, to $19.2 million in January.

There’s more on the horizon. Many in the art world are gearing up for 2026, the 250th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence (on July 4, 1776), with institutions across the country set to host exhibitions and events that will showcase historical American art.

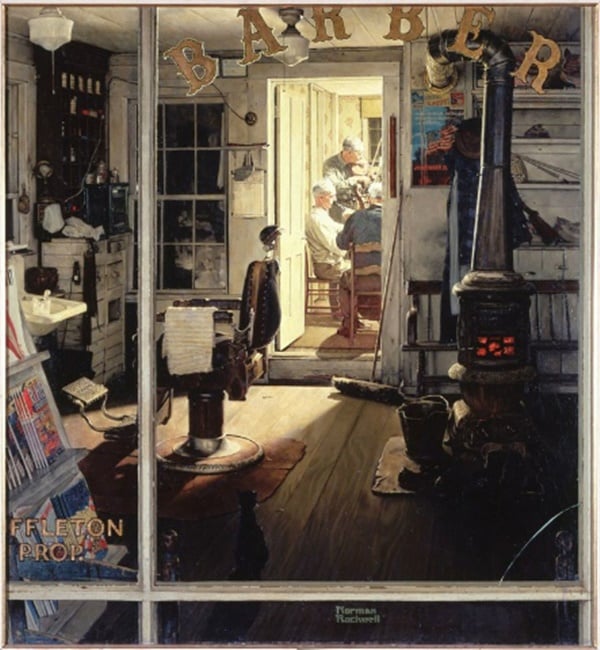

Norman Rockwell, Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1959). Courtesy: Berkshire Fine Arts.

“The semiquincentennial will generate and nurture new scholarship and new engagement and, I believe, it will accelerate the rebound of the traditional American art market,” said dealer Andrew Schoelkopf, whose New York gallery specializes in American art.

Schoelkopf is among the cadre of dealers, advisors, and auction experts hoping for history to repeat itself. Back in 1976, the 200th anniversary of the United States led to a surge of interest in classic American material.

“The American art collecting category wasn’t really a thing until the bicentennial in 1976,” said Peter Koval, an art advisor in the field. “All of a sudden there was fervor around all things that were inherently American.”

“It was a huge reawakening,” said Katharine Wright, curator of the American Federation of Arts, whose exhibition “Making American Artists: Stories from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1776–1976” is currently touring the country. “I am hoping this will be the same next year.”

Auspicious Beginnings

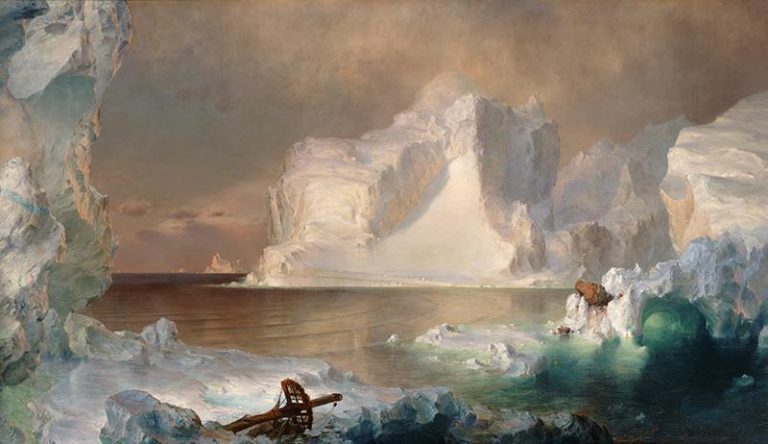

In 1975, paper magnate Jack Warner purchased two Hudson River School masterpieces, Thomas Cole’s 1826 Falls of the Kaaterskill and Asher Durand’s 1853 Progress (The Advance of Civilization). The works would become the cornerstones of his formidable collection. In 1979, an 1861 landscape, The Icebergs, by Fredric Edwin Church (1826-1900) went for $2.5 million, then the highest price paid for an American artwork.

Other titans of industry followed Warner into the field. Some of the biggest auction sales took place in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Bill Gates bought Winslow Homer’s 1885 seascape Lost on the Grand Banks for more than $30 million in 1998, setting a new record for an American painting. The following year, he snapped up Polo Crowd (1910) by George Bellows for $27.5 million at Sotheby’s. Albert Bierstadt’s Indians Spear Fishing (1862) sold for $7.3 million at Christie’s in 2008, still the auction record for the artist.

Though the segment never recovered from the financial crisis, new museums have helped boost interest and prices. Alice Walton, the billionaire founder of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Ark., paid record $44.4 million for Georgia O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1932) at Sotheby’s in 2014. The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, which is set to open in Los Angeles next year, acquired Norman Rockwell’s Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1950) from the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Mass., for an estimated $25 million in 2018.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1932). Courtesy of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Ark.

Despite those headlines, the historical American art field languished. In those years, the auction houses offered all kinds of lots in semi-annual American art sales, dating from the Revolutionary War to World War II. “You would find Albert Bierstadt in the same sale as Georgia O’Keeffe,” Tylee Abbott, Christie’s head of American art, said. “And the collectors used to buy and collect American art as the story of American history.”

The audience remained primarily domestic, a limiting factor at a time when new billionaires from Russia, China, and the Middle East were driving prices for postwar and contemporary American art into the stratosphere.

Many of the greatest American artists, who are ensconced in art history and major museum collections, are laughably undervalued today.

Church’s annual auction sales totaled just $177,800 in 2024, according to the Artnet Price Database. For his part, Cole (1801–1848), the founder of the Hudson River School, peaked in 2003 at $1.69 million in annual sales.

Thomas Cole, Mount Chocorua, New Hampshire (1827). Courtesy: Christie’s

These figures are especially jarring compared with ultra-contemporary art prices. Two days ago, a 2018 painting by South African painter Lisa Brice (born in 1968) sold for $6.8 million at Sotheby’s in London.

‘Lack of Understanding’

American art faces structural and cultural challenges, experts say. Understanding the situation requires taking a step back.

Traditional American art is an umbrella term for a massive swath of art history. Spanning more than 150 years, it begins with the close of the 18th century, as professionally trained American artists begin to appear, and ends with the ascendence of American Modernism around World War II.

Within this timeframe, American artists worked in many genres: the Hudson River School, still life, genre painting, Impressionism, Modernism, illustration, realism, and magic realism. Some of those areas have regional variations, like the different Impressionisms of the Boston School and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. There’s also early-20th-century Ashcan School urban painting and Western subjects in a variety of styles.

Each one of these sub-genres is a separate collecting category, with its own scholarship and connoisseurship.

Winslow Homer, On the Beach at Marshfield (ca. 1872) from the Wolf Family Collection. Courtesy: Sotheby’s

“There’s been a lack of understanding of the field broadly and therefore all of those categories get lumped together in one bucket, which is not really how people collect,” Schoelkopf said.

Further complicating the situation is the lack of available data. A big chunk of sales is done privately. Christie’s Abbott said that the company sold as much American art privately as it did at auction in 2024. These results are absent from auction databases used for valuations.

There’s also a vast gap between artists’ records sold privately and at auction.

In January, Christie’s trumpeted its record auction result for Cole‘s 1827 painting Mount Chocorua, New Hampshire: $1.62 million. However, much higher prices have been paid privately for Cole over the years. In 2011, when some of Jack Wagner’s collection returned to the market, Cole’s Falls of the Kaaterskill reportedly sold for more than $35 million. In 2021, the Ahmanson Foundation acquired Cole’s monumental Portage Falls on the Genesee (1839) for $12 million on behalf of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, Calif.

Asher Durand, Progress (The Advance of Civilization (1853). Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Durand, the acclaimed Hudson River painter, is another useful case study. His $967,500 auction record was set in 2017, for the 1848 painting Mountain Stream. But in 2005, the New York Public Library privately sold its 1849 Durand, Kindred Spirits, for more than $35 million to Walton. In 2011, an anonymous buyer paid about $40 million for Duran’s Progress (The Advance of Civilization) from Wagner’s collection and donated it to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Va.

Squaring these figures can be confusing, complicating appraisals and making collectors hesitant to part with their art.

“They don’t have enough market intelligence to make an informed decision,” Schoelkopf said. “A lot of erroneous figures are floating around.”

Winning Formula

Placing historical American art in the context of more fashionable 20th- and 21st-century art has been a winning formula for market makers. I remember Mnuchin gallery’s 2020 show that paired Ab-Ex master Mark Rothko with Church. Aptly titled “Church and Rothko: Sublime,” it brought together 27 oil paintings to spellbinding effect.

In the past decade, Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips began including major works by American modernists, who worked into the second half of the 20th century (like O’Keeffe and Hopper) in their marquee New York auctions in November and May.

“Most people are struck by how contemporary the work looks,” said art advisor Todd Levin. “A Hopper looks great in a minimalist collection.”

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington (The Lansdowne Portrait), 1796. Courtesy: American Federation of Arts

The market has been trying to bridge centuries by catching up with shifts in scholarship and interpretation in the field.

“Now we look at the cannon in a different way,” Schoelkopf said. Markets for African American artists of the era “have exploded,” he added, listing Edward Bannister (1828-1901), Robert Scott Duncanson (1821–72) and Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937).

Some of these historical figures are included in “Making American Artists,” the American Federation of Arts show. There’s Gilbert Stuart’s iconic 1876 portrait of George Washington and many female and gay artists, and artists of color, such as Bannister and Tanner. The show’s two-year tour to six venues across the country is scheduled to end in January, just as America’s 250th anniversary begins. Sotheby’s and Christie’s have already begun looking for material for the American art sales that are scheduled for that month.

“We fully plan to capitalize on that,” Sotheby’s head of American art, Stephany Morris, said of the semiquincentennial. “We have quite a few irons in the fire.”

[ad_2]

Source link