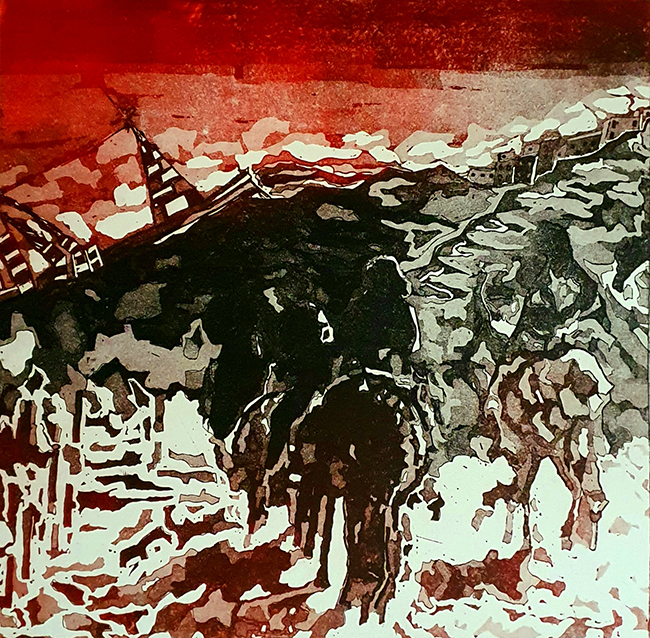

Katerina Tsitsela’s work doesn’t sit neatly in one corner of the art world. She moves between painting and engraving, not to switch gears, but to deepen the same question: what does it mean to feel? Her art is rooted in human emotion, but it doesn’t scream or dramatize. Instead, it opens quiet doors. Her focus isn’t on the world as it looks but on the world as we experience it from the inside out.

Tsitsela calls these “internal landscapes”—mental and emotional spaces shaped by anxiety, grief, reflection, and the need to survive. These are not literal depictions. They are not portraits of people. Yet somehow, they feel personal. A certain shade of blue might suggest a lingering sadness. A jagged black line could trace the edge of a thought that never found its way to speech.

Her work is not about resolution. It’s about holding space for the things we often keep buried.

Imaginary Cities, Real Emotions

In one of her poetic descriptions, Tsitsela writes:

A city is born in the silence of color

harsh lines hold it upright,

like a thought never spoken.

It’s a simple image, but it carries weight. A city—usually loud, sprawling, full of life—is here imagined as something quiet, almost hesitant. The “harsh lines” that hold it up speak to structure, to control. But the feeling underneath is different. This is not a place you can visit with a map. It’s more like a dream, or a memory that won’t settle.

These cities are built not from bricks but from internal states. She pulls inspiration from the concept of “Invisible Cities,” echoing Italo Calvino’s reflections on imaginary places and their emotional significance. Her cities don’t exist on any physical landscape, but they are real in another sense: they reflect the architecture of the soul.

The Silence of Color

Color in Tsitsela’s work doesn’t play a decorative role. It carries emotion the way music carries mood. She often starts from silence—literal or visual—and then lets the color speak. Sometimes it’s subdued. Other times, it hits like a chord. But it’s never accidental.

Each hue feels selected with care, not to impress but to express. You might find earthy tones that feel heavy, or sharp contrasts that hint at dissonance. In some works, light is used sparingly, as if it must be earned. In others, darkness isn’t something to fear, but something to learn from.

Color, for Tsitsela, is emotional terrain.

Printmaking as Perception

Her printmaking works operate with the same philosophy. Unlike the bold strokes of painting, engraving is slower. It demands precision, repetition, restraint. For Tsitsela, it’s not a lesser form. It’s a different kind of conversation—with herself and with the viewer.

Where painting might evoke a rush of feeling, engraving draws you in, bit by bit. The textures she creates in print mirror the process of working through an emotion—layered, deliberate, sometimes raw. Each etched line is like a whisper from a deeper place.

The mix of mediums in her work allows her to explore different aspects of perception. Some feelings are loud and demand to be painted. Others are quiet and need to be carved.

Mental States as Landscape

What makes Tsitsela’s work resonate isn’t that it shows a clear message. It’s that it mirrors the complexity of being human. The way a mind can wander. The way a memory can loop. The way anxiety can press down or float just out of reach.

Her landscapes are not of nature, but of thought. They suggest mental weather—storms of doubt, long winters of grief, rare bright days. They chart no path, but they ask questions: Where am I right now? What am I carrying? Can I name it?

The strength of her work lies in that tension—between form and formlessness, between knowing and not knowing.

Art as a Mirror, Not a Window

Katerina Tsitsela’s art doesn’t provide answers. It reflects states of being. In her paintings and prints, you might not always find clarity, but you’ll find honesty. Her work recognizes that being alive means holding contradiction. That beauty and discomfort often live side by side. That cities can be silent. That lines can speak.

She doesn’t ask you to understand her work. She asks you to feel it—and, in doing so, to confront your own invisible landscapes.