Pop Art didn’t just happen. It arrived with a bang—a colorful, ironic, and sometimes loud answer to the seriousness of modernism. Born out of a post-war world swimming in advertising, television, and celebrity culture, Pop Art held up a mirror to the times. It asked: What if art isn’t just about inner turmoil or abstract ideals? What if it’s about Coca-Cola bottles, comic books, and movie stars?

The movement took shape in the mid-1950s in Britain before finding its full voice in the United States during the early 1960s. British artists like Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi were among the first to play with images from consumer culture. Hamilton’s 1956 collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? is often seen as one of the first true Pop Art pieces. It mashed together magazine clippings, advertising, and irony to create a comment on postwar affluence and the rise of media saturation.

But it was in the U.S. that Pop Art went big. America had the booming economy, the television sets, the fast food, the glossy magazines. It also had artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and James Rosenquist—names now inseparable from Pop Art itself.

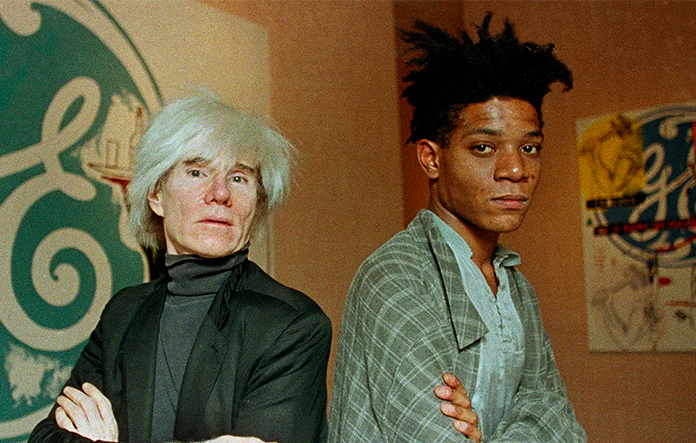

Andy Warhol may be the most famous. He painted soup cans, Brillo boxes, and screen-printed portraits of Marilyn Monroe not because he adored them, but because he was interested in how we consume images. His studio, The Factory, became a hub for creatives, socialites, and cultural outsiders. Warhol turned repetition into rhythm, celebrity into symbol, and questioned the meaning of originality in a world that was increasingly about mass production.

Roy Lichtenstein took comic book panels and blew them up to massive scale, complete with dots mimicking cheap newspaper printing. His work felt mechanical on purpose—clean, ironic, and detached. By turning something considered “low culture” into high art, he forced people to rethink what art could be and where it came from.

Pop Art wasn’t limited to painting. Sculptors like Claes Oldenburg made soft hamburgers and giant ice cream cones. Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nudes series flattened the female body into something like a billboard. Rosalyn Drexler, often under-recognized, used collage and bright colors to tackle gender, violence, and media stereotypes.

Critics were divided. Some dismissed it as shallow or gimmicky. Others saw it as a sharp critique of consumerism and the dehumanizing effect of mass media. Either way, Pop Art left its mark. It blew open the doors on what could be considered art and helped dissolve the boundary between high and low culture.

By the late 1960s, the movement began to fade, absorbed into other styles or eclipsed by minimalism and conceptual art. But its impact never really went away. Pop Art paved the way for everything from street art to graphic design. You can still see echoes of it today—in fashion, music videos, advertisements, and digital art.

In short, Pop Art was never just about soup cans. It was about questioning value, authorship, desire, and identity in a world dominated by images. And it did all that while looking fun.